Fieldnotes by Bianca Hisse and Christian Danielewitz

The Longyear River swells with rushing meltwater. Glaciers creak, valleys shift, and the seismic sensors outside Longyearbyen register the imperceptible vibrations of thawing ice, pressure changes, or distant calving events. It is the ambient noise of the Arctic, but it feels like a kind of breathing. To listen here is to hear the planet exhaling. Small vernaculars of water emerge to the surface: inscribed in sounds and sediments, Svalbard is a chronicle written in tremor. In this landscape, the river performs its refusals and disclosures, troubling long-standing colonial imaginaries of emptiness and peripherality that have cast Svalbard as a laboratory of modernity, as if the Arctic were a blank page to be written on.

Drill cores scattered along the archipelago are material indicators of Svalbard’s long history of scientific inquiry, resource exploration, and colonial territoriality. Extracted during decades of geological surveying, these cores constitute a dispersed, eroding archive of extraction: each sample reflects both a moment of intervention into deep time and a trace of state and industrial ambition onto the landscape. Drill cores are evidence of Arctic modernity’s twin ambitions – to know the land, and to take from it. Simultaneously instruments of knowledge production and remnants of extractive desire.

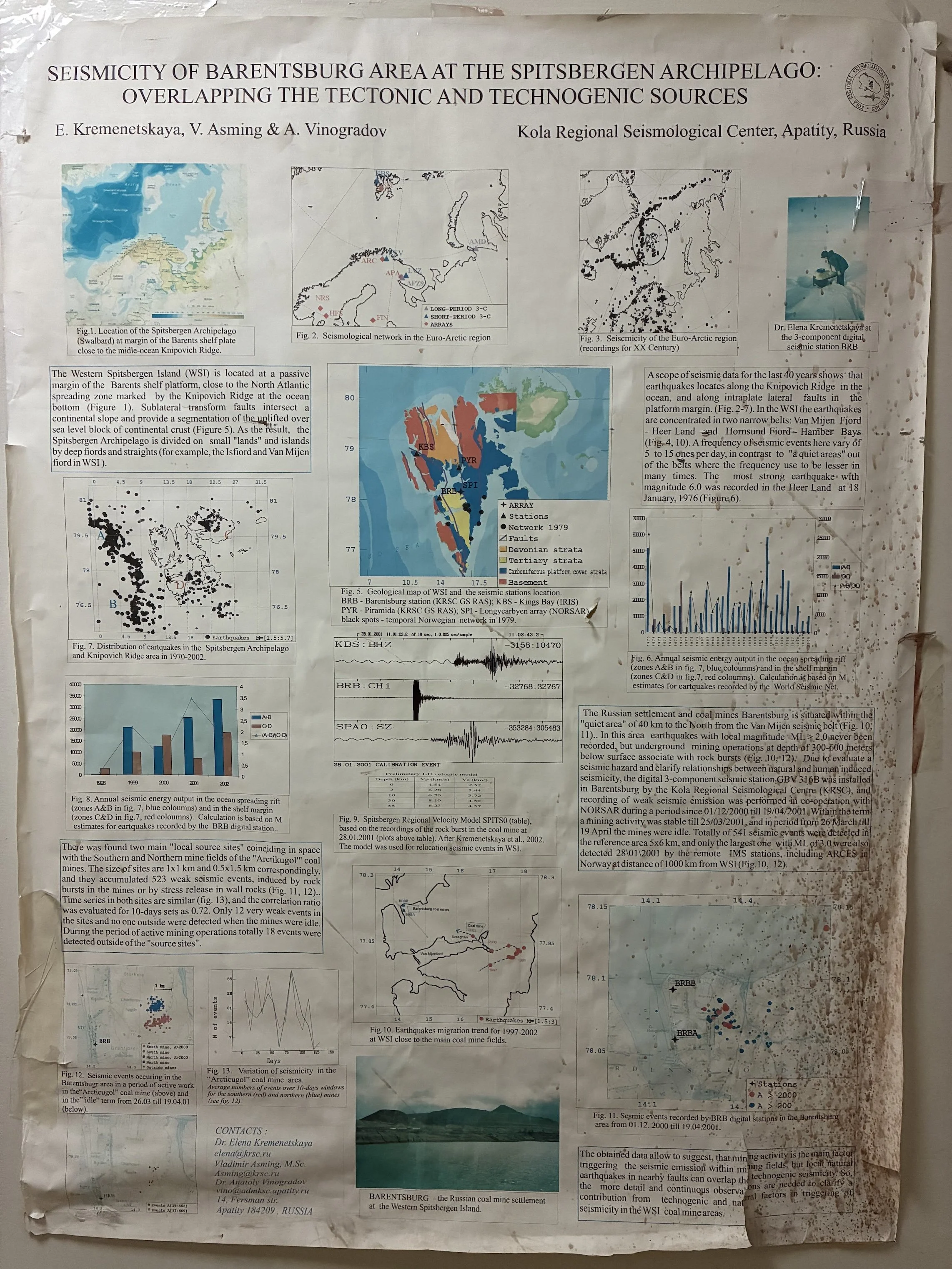

A few hours west of Longyearbyen lies Barentsburg, a living fossil of a coal-mining town, operated by the state company Arktikugol. The Russian settlement feels like a palimpsest of Soviet modernity, where extraction and ideology continue to overlap. Along the waterfront, conveyor belts rust beside new signs advertising “Arctic tourism.” A mural of a coal miner holding up a glowing piece of coal greets visitors: “Miner, with you work-worn hand you give warmth and light to everyone”.

On the outskirts of the settlement lies an outpost of the Kola Science Centre. Here we meet Dr. Boris Gvozdevsky, a physicist from the Polar Geophysical Institute in Apatity, Murmansk. Gvozdevsky oversees the Barentsburg cosmic ray station, which has operated continuously since 1964 – a remnant of the Soviet scientific presence in the Arctic that persists today as part of a network measuring cosmic radiation and solar activity.

The laboratory itself is modest: three wooden huts standing on the hillside, their neutron monitors humming faintly above the fjord, overlooking heaps of coal and thawing mud. Gvozdevsky explains how high-energy particles from the Sun and deep space collide with the atmosphere, producing cascades of secondary radiation that are captured by his detectors.

Inside the research station, shelves hold jars of preserved lichen and moss beside rock samples, the walls hung with crumbling scientific maps. Outside, coal trucks pass on their way to the port. From the hill, we can see the contrast clearly: a cosmic observatory built within an extractive landscape, both sustained by the same energy grid. The scene feels emblematic of the Arctic itself – a place where science and empire share an infrastructure, where the pursuit of knowledge and the extraction of value proceed in parallel, each legitimising the other.

Science, here, is not opposed to empire but one of its extensions. The long continuity of measurement – from the Soviet era to today’s Russian Arctic ambitions – sustains a geopolitical rhythm as steady as the neutron monitor’s pulse. Data becomes a form of presence; the act of observing is also an act of possession. To measure the Arctic is to claim it, to archive it in graphs and samples, to draw its movement into the language of science. Yet beneath these instruments runs another kind of time – glacial, planetary – a duration that erodes every ideology, no matter how precise its instruments.

In October, as the dark season draws near, fellow artists James and David join us on a field trip to the Longyear Glacier. We carry hydrophones and portable recorders, following the river of meltwater upstream. We lower the microphones into the flow, and through the headphones comes a rush of sound; the gurgle of under-ice channels, and, beneath it, a low steady pulse. While Gvozdevsky’s instruments catch particles arriving from deep space, ours listen to the freezing and thawing of ice, the slow unravelling of a frozen archive. Both forms of measurement translate time into frequency – one registering solar events in distant atmospheres, the other the thaw of a glacier on a warming planet.

Science and empire both seek to master time – to capture its flow, to discipline its unpredictability into data and control. But the glacier’s voice is continuous, untranslatable, indifferent. In its shifts and surges, science and its ostensible subject begin to dissolve into one another, like ice into water, water into sound.

Listening to the glacier, one realises that the way of time is one of persistence. The Arctic teaches this through its ambient noise: the rush of meltwater, the static of radiation, the groan of shifting ice. Time here unfolds as vibration, as background noise, as the unending conversation between the planet and those who record it.